Theft from the Hot Zone

When a Ft. Detrick researcher flew to NYC with a deadly virus sample in his pocket.

On April 29, Health and Human Services (HHS) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) paused work at a high-risk infectious disease lab, a “hot zone” at Fort Detrick, Maryland, citing chronic safety issues. The closure was triggered after a researcher deliberately poked a hole in a co-worker’s biocontainment suit after a dispute.

“No more lab-generated pandemics!” said the new NIH director, Jay Bhattacharya, PhD, MD, about the reason behind the shutdown. [1] He noted that it took almost two months for this incident to be reported to HHS leaders.

It’s important to realize that this incident is not a one-off event. It’s one of many examples where researchers viewed safety regulations as a hassle that requires unnecessary paperwork. [2] These risks will only increase as more high-risk infectious disease labs are built, sometimes staffed by undertrained and inadequately screened employees.

Journalists covering lab leaks have often asked the question: At what point do unsafe labs pose more of a health risk than the diseases the institutions are trying to cure?

My interest in lab security began while working on “Bitten.” The book’s main subject, Dr. Willy Burgdorfer, was a Cold War bug-borne bioweapons researcher who worked for the NIH at Fort Detrick and Rocky Mountain Labs. On several occasions, he said that the Russians had stolen bioweapons samples from a lab where he worked. He also said that he was questioned twice by government investigators about the missing samples. Given that Burgdorfer had money issues, a needy mistress, and a secret Swiss bank account, I felt compelled to investigate whether he was involved in an agent theft.

First, I searched newspaper archives and found a possible lead.

On April 22, 2009, Katherine Heerbrandt of The Frederick News-Post published a story about missing Venezuelan Equine Encephalitis Virus (VEEV) vials. [3]

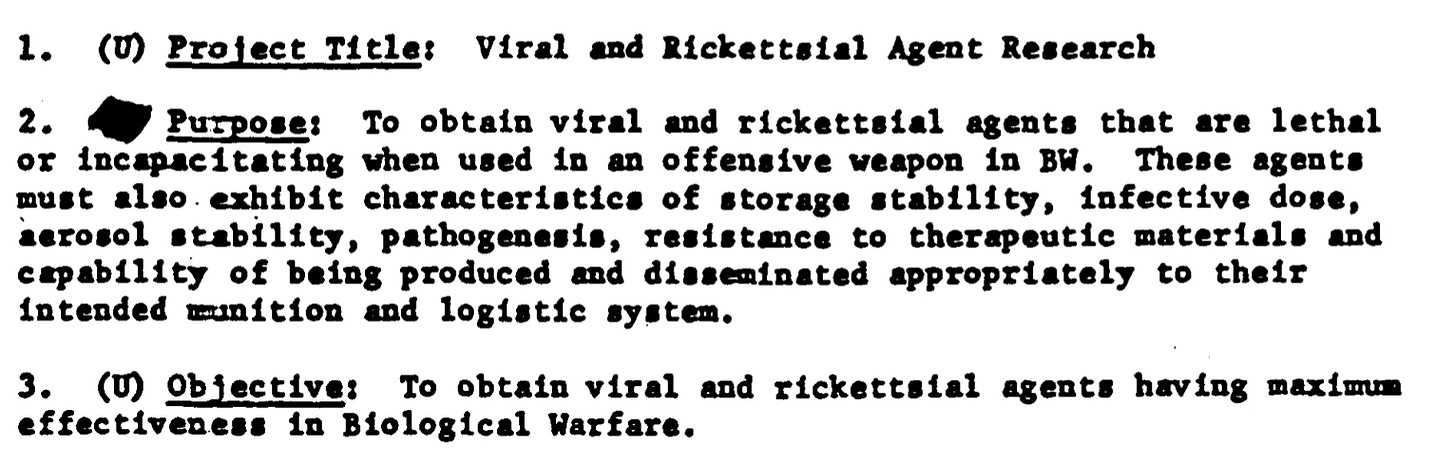

I knew from my research that VEEV was weaponized by the United States and the Soviet Union during the Cold War. Early on, Burgdorfer inoculated ticks with equine encephalitis virus as part of the tick and mosquito weaponization program. [4] Later, the military figured out a more efficient delivery mechanism—they aerosolized VEEV so it could be sprayed over large areas. [5] Even though the US bioweapons program was shuttered in 1969, there are still small samples of VEEV stored in freezers around the country.

Today, VEEV is considered a major biothreat. It can cause severe disease in humans and animals. Symptoms include fever, malaise, and vomiting. Infections can invade the central nervous system, causing confusion, seizures, and death. (Though the vials in this instance carried an attenuated VEEV vaccine, the weakened virus can be brought back to life in culture or in a living host.)

The cover-up

In 2009, concerns over the missing vials soon faded after a Fort Detrick spokesperson, Caree Vander Linden, told The Washington Post:

“…several years ago, an entire freezer full of biological samples broke down and all the samples had to be safely destroyed.”

“We’ll probably never know exactly what happened,” an Army official told reporters. “It could be the freezer malfunction. It could be they never existed.”

But an Army investigation report that I obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request in 2021 revealed a more disturbing story. Three VEEV vials went missing from a freezer sometime after 1976, when they were first logged into Fort Detrick’s virology suite. The report, published in 2012, went on to say that a Fort Detrick researcher took one of the stolen vials of VEEV vaccine from the lab, slipped it in his pocket, and traveled via airplane from Maryland to New York, where he gave it to a researcher friend.

[View the investigation timeline here and the Army report here.]

Even after an investigation where hundreds of employees were questioned, the scientist didn’t confess to the theft.

“Dr. [redacted] made no effort to return the vial and offered it to a colleague to use in a laboratory experiment. Dr. [redacted] was interviewed and stated he knowingly possessed the vaccine. Dr. [redacted] related he intended to keep the vaccine and only turned it in to his supervisor after he was confronted about it.”

According to the Army report, the researcher broke two federal laws: “Theft of Biological Select Agents and Toxins” and “Transportation of Stolen Property/Biological Select Agents and Toxins.”

These rules were established to prevent catastrophic lab leaks, and there are a number of scenarios of what could go wrong with a deadly virus in your pocket, including:

1. What if a TSA worker in the airport security line opened the vial and sniffed it?

2. What if the vial fell out of the researcher’s pocket on the plane, and a child opened it?

3. What if a helicopter hit the plane and released the agent?

4. What if the colleague to whom he gave the vial was a covert foreign agent?

No consequences

Dr. [redacted] surely knew the consequences of his action, given the outcome of the 2003 case against Dr. Thomas Butler, a researcher at Texas Tech University, who was convicted on 47 of 69 charges involving the transport of vials of plague bacteria. He was sentenced to two years in federal prison. [6]

Yet, the virus-stealing researcher doubled down on secrecy during the investigation, and his identity would still be a mystery if it weren’t for an anonymous email tip.

So, who was this researcher? We don’t know. Was he punished, and is he still on the government payroll? We don’t know. And what happened to the two other VEEV vials? We don’t know. We only know from my FOIA request that an Army judge determined that this researcher wouldn’t be sent to jail because there was “no criminal intent.”

Add this to the holey lab suit incident, and it demonstrates a pattern of willful disregard of laws designed to protect public health. I support the HHS/NIH initiative to review and reset the “above the law” culture at these high-risk research facilities.

***

Kris Newby is an award-winning medical science writer and the senior producer of the Lyme disease documentary UNDER OUR SKIN. Her book BITTEN: The Secret History of Lyme Disease and Biological Weapons won three international book awards for journalism and narrative nonfiction. Previously, Newby worked for Stanford Medical School, Apple, and other Silicon Valley companies.

If you’ve found this content useful, please consider supporting it through a small paid subscription. While you can read my posts for free, a paid subscription helps underwrite this independent research. And it keeps it free for those who can’t afford to pay.

Image credit: Kris Newby/ChatGPT

Sources:

1. https://x.com/NIHDirector_Jay/status/1920241322167865389

2. https://krisnewby.substack.com/p/little-shop-of-horrors-accidents

4. Burgdorfer W, Pickens EG. A technique employing embryonated chicken eggs for the infection of argasid ticks with Coxiella burnetii, Bacterium tularense, Leptospira icterohaemorrhagiae, and western equine encephalitis virus. J Infect Dis. 1954 Jan-Feb;94(1):84-9. doi: 10.1093/infdis/94.1.84. PMID: 13143226.

5. Lundberg L, Carey B, Kehn-Hall K. Venezuelan Equine Encephalitis Virus Capsid-The Clever Caper. Viruses. 2017 Sep 29;9(10):279. doi: 10.3390/v9100279. PMID: 28961161; PMCID: PMC5691631.

6. Chang, Kenneth, “Scientist In Plague Case Is Sentenced To Two Years,” New York Times, March 11, 2004. https://www.nytimes.com/2004/03/11/us/scientist-in-plague-case-is-sentenced-to-two-years.html

###

Seriously makes me wonder about all the tick borne illnesses. I had two, and they just about killed me. Mostly because it took two years to figure it out.

Now, I stay out of the woods. So sad.

hard to love this story. I read similar stories years ago, when a reporter testified that lab leaks happen every 3 or so days. Days ! Aren't we lucky we are still alive?