Little Shop of Horrors: Accidents at a Bioweapons Lab

When genetically engineered organisms are released on a population without natural immunity, it can lead to disease, death, and pandemics.

Willy Burgdorfer was a Swiss American tick expert who developed bug-borne weapons for the U.S. military during the Cold War. Most of his assignments came from the Biological Warfare Laboratories at Fort Detrick and involved working with the tiny vampires of the animal kingdom — fleas, ticks, and mosquitoes. The military strategy behind the use of these arthropods was:

In 1953 the Biological Warfare Laboratories at Fort Detrick established a program to study the use of arthropods for spreading antipersonnel BW [bioweapons] agents. The advantages of arthropods as BW carriers are these: they inject the agent directly into the body, so that a mask is no protection to a soldier, and they will remain alive for some time, keeping an area constantly dangerous. [1]

Burgdorfer worked on the front-end of the weaponization process, designing experiments to determine:

1. Can arthropod reproduction rates be accelerated so that these bugs could be mass produced by the millions?

2. What are the best combinations of arthropods and microbes for use in cold climates (Russia and Korea) and the tropics (Cuba and Vietnam)?

3. For each arthropod-microbe combo, what are the optimal lethal or incapacitating infection levels for harming humans?

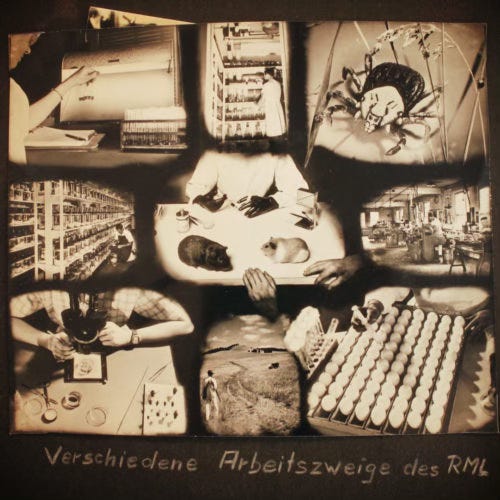

Rocky Mountain Laboratories in Hamilton, Montana.

It was dangerous work, and even though Burgdorfer was a meticulous researcher, there were several serious accidents in his lab at the Rocky Mountain Laboratories in Montana. One resulted in harm to himself, another to a lab assistant. Other mistakes put the public at risk of exposure to two deadly pathogens — the yellow fever virus and the plague bacterium. Yet none of these accidents were ever reported to the public.

Here is a list of known lab accidents that happened on Willy Burgdorfer’s watch. [2]

The plague-in-the-mail incidents

One of Burgdorfer’s first Fort Detrick projects was to figure out how to mass produce fleas, feed them with plague bacteria, and then package them in tubes that could be dispersed over enemy territory in cluster bombs.

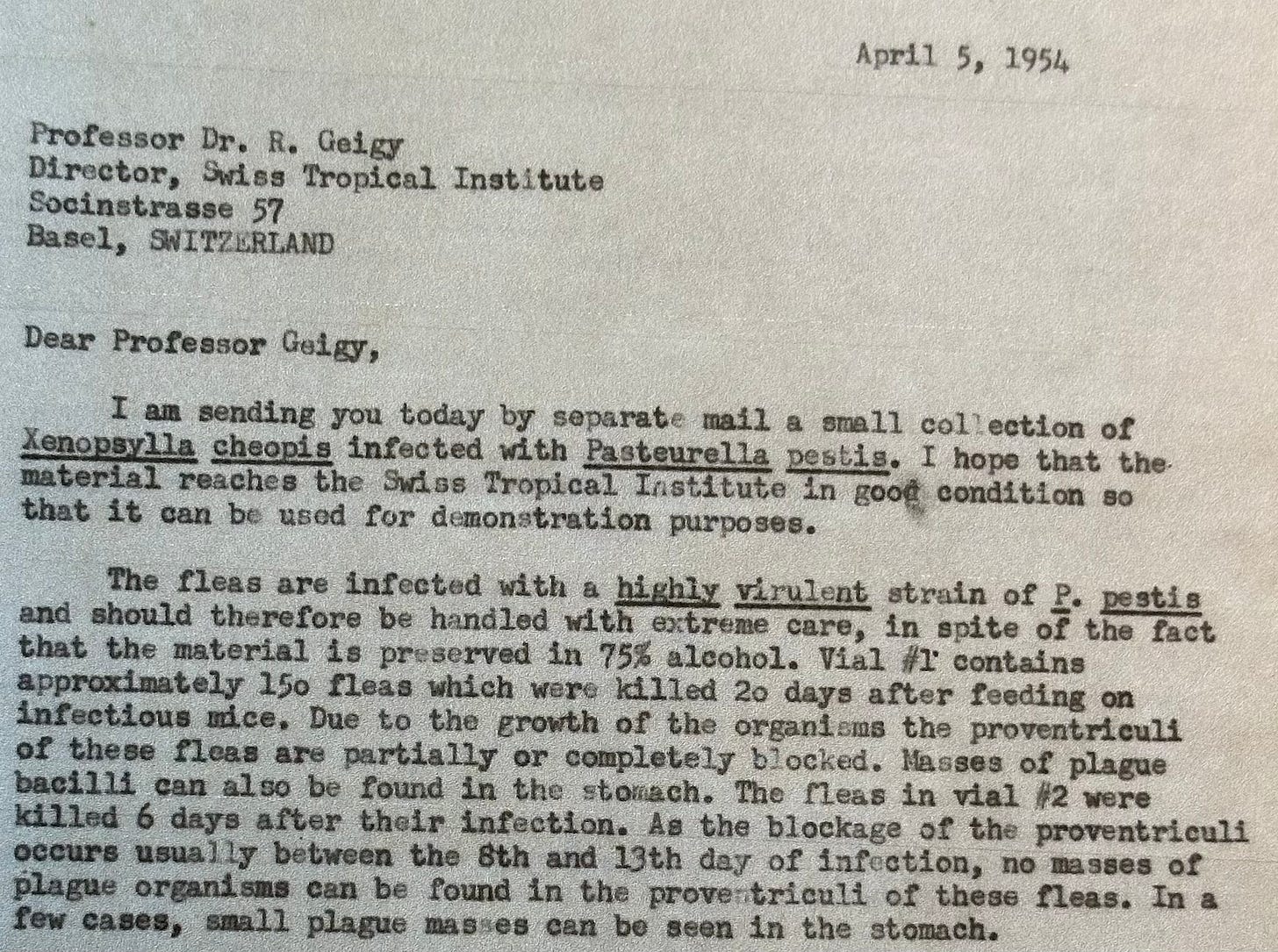

In a letter dated April 5, 1954, Burgdorfer wrote to his mentor, Rudolf Geigy at the Swiss Tropical Institute: “I am sending you today by separate mail a small collection of Xenopsylla Cheopis (oriental rat fleas) infected with Pasteurella pestis (renamed Yersinia pestis). I hope the material reaches the Swiss Tropical Institute in good condition so that it can be used for demonstration purposes. The fleas are infected with a highly virulent strain of P. pestis and should therefore be handled with extreme care, in spite of the fact that the material is preserved in 75% alcohol.”

In addition, on November 2, 1954, his secretary accidently sent 75 fleas infected with Yersinia pestis through the U.S. Postal Service to Dale Jenkins at Fort Detrick.

Yersinia pestis, aka “The Plague” or “The Black Death,” killed millions of people in Europe during the Middle Ages. Shipping dangerous pathogens through the mail poses risks of releases through vehicle accidents, theft, or hungry rodents. The seriousness of this was reinforced in 2004, when Dr. Thomas Butler from Texas Tech University was sent to jail for two years, in part, for the illegal transport of plague samples inside and outside of the country. [3]

The infected tick shipments

During the Cold War, Rocky Mountain Laboratories maintained the largest collection of living ticks in the United States. Burgdorfer oversaw the shipment of tick colonies to other bioweapons contractors and foreign collaborators. Before sending ticks out, he would test a few in each batch to make sure they weren’t harboring any dangerous pathogens. These batches would range from a dozen to 10,000-plus ticks.

By Burgdorfer’s own admission, his screening process wasn’t fool proof. And in the 50s and 60s, his lab wasn’t equipped to detect viruses. He often told people, “There is no such thing as a clean tick.”

This proved to be true on December 31, 1954, when Burgdorfer sent two batches of supposedly clean ticks to Dale Jenkins at Fort Detrick and H.B. Newcombe, an Ontario-based expert on radiation-induced genetic changes in bacteria. When Burgdorfer discovered his mistake, he sent out warnings to the recipients that some of the ticks were infected with an unknown species of relapsing fever bacteria (spirochetal cousins of Borrelia burgdorferi, the causative agent of Lyme disease). He guessed that it was Borrelia duttoni from sub-Saharan Africa, which can cause serious neurological symptoms, intermittent high fevers, death, and long-term brain impairment. [4]

Another time, a new lab technician in Burgdorfer’s lab was bitten by one of the relapsing fever ticks. He subsequently became very ill and had to resign.

The monkey blood accident

In 1958, Burgdorfer was asked by Dale W. Jenkins, chief of Fort Detrick’s entomological warfare branch, to feed mosquitos with an extremely deadly strain of the yellow fever virus, obtained from a dead Red Howler monkey from Trinidad, to determine the lethal dose of microbes required to kill of 50% of the monkeys.

While Burgdorfer was on a trip to Fort Detrick, his lab assistant, Tony Mavros, was in charge of collecting monkey blood infected with yellow fever virus so that it could be fed to other mosquitoes. As he started the process of draining blood from a monkey, it escaped, then spewed “hot” infected blood all over Mavros.

In reading his letters, Burgdorfer seemed to be terrified that Mavros would die. “I am quite anxious to hear from Tony, especially about the development of the YF (yellow fever) monkey affair! Tony should send me each week a proper report — so far, I didn’t receive anything,” wrote Willy to his wife.

The rabbit urine accident

A few years after the U.S. biological weapons program was cancelled, Willy Burgdorfer began investigating the cause of the mysterious disease outbreak around Lyme, Connecticut. After analyzing ticks and human blood in the area, he discovered two organisms that he thought could be making people sick — a spirochete and a rickettsial bacteria. He was told by some unnamed person in power to hide the existence of the rickettsia, possibly a bioweapon, nicknamed “Swiss Agent USA.” (Read more here: https://www.statnews.com/2016/10/12/swiss-agent-lyme-disease-mystery/)

In his frenzy to gather evidence on this discovery, he worked long hours on experiments, many of which involved attaching infected ticks to rabbits. In March 1982, he went into his lab to clean animal cages and urine from an infected rabbit splashed in his eyes. Afterwards he came down with Lyme disease.

He became so sick from the infection that he had to file for worker’s compensation with his employer, the National Institutes of Health. He documented multiple Lyme disease rashes under his arm, which looked very similar to those on his infected rabbits. Ultimately, he ended up retiring early and developed Parkinson’s disease (though there is no way to prove these symptoms were caused by Lyme disease or the mystery rickettsia.)

When I asked him if he thought the Parkinson’s symptoms were caused by Lyme disease he angrily replied, “Ask the doctors.”

Burgdorfer’s bullseye rashes after a Lyme infection.

Why this matters

During the Cold War, laboratory safety standards weren’t as stringent as they are now. But even today, lab accidents happen. And when genetically engineered organisms are released on a population without natural immunity, it can lead to disease, death, and pandemics.

The history of accidents in Burgdorer’s lab supports one hypothesis that I present in my book, “Bitten” — that Burgdorfer might’ve sent “unclean” ticks harboring exotic pathogens to bioweapons contractors working with ticks, including Plum Island, the anti-animal bioweapons lab a few miles from ground zero of the Lyme-area outbreak. Could this be what started the outbreak of three novel tick-borne diseases in the late 60s near Lyme, Connecticut? (To read more about the release of hundreds of thousands of radioactive ticks on the Atlantic Bird Flyway, see: “The Rise of the Lone Star Ticks.”) https://krisnewby.substack.com/p/the-rise-of-the-lone-star-tick

These kinds of accidents can have long-lasting effects on the environment and human/animal health, and this is why I continue to push for declassification of these decades-old military secrets. Knowledge of where engineered organisms escaped into the wilds will save lives and research dollars. If these microbes have been genetically altered, we need a more intelligent approach to disease control. If the military harmed U.S. citizens through irresponsible experiments, they should fix it.

For more on Willy Burgdorfer and tick weaponization, read “BITTEN: The Secret History of Lyme Disease and Biological Weapons.”

For details on other lab accidents, read Alison Young’s excellent book, “Pandora’s Gamble: Lab Leaks, Pandemics, and a World at Risk.” https://www.hachettebookgroup.com/titles/alison-young/pandoras-gamble/9781546002932/?lens=center-street

Kris Newby is an award-winning medical science writer and the senior producer of the Lyme disease documentary UNDER OUR SKIN. Her book BITTEN: The Secret History of Lyme Disease and Biological Weapons won three international book awards for journalism and narrative nonfiction. Previously, Newby worked for Stanford Medical School, Apple, and other Silicon Valley companies.

If you've found this content useful, please consider supporting it through a small paid subscription. While my posts are free, your paid subscription helps underwrite this independent research. It also helps keep it free for those who cannot afford to pay.

###

[1] U.S. Army Chemical Corps, “Summary of Major Events and Problems (Fiscal Year 1959),” p. 100–104. https://www.osti.gov/opennet/servlets/purl/16006843-5BAfk6/16006843.pdf

[2] All lab accident data is obtained from the “Willy Burgdorfer Collection of Lyme Disease Research Materials. https://uvu.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/Burgdorfer

[3] Chang, Kenneth, “Scientist In Plague Case Is Sentenced To Two Years,” New York Times, March 11, 2004. https://www.nytimes.com/2004/03/11/us/scientist-in-plague-case-is-sentenced-to-two-years.html

[4] Jakab Á, Kahlig P, Kuenzli E, Neumayr A. Tick borne relapsing fever - a systematic review and analysis of the literature. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2022 Feb 16;16(2):e0010212. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0010212. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8887751/

Wow, what a “confidence” boost your article gives me as I sit here 1/2 the man I used to be. Bb, Rr, Bartonella, TBRF. 🤯

Loved your book & thank you for keeping our BW community in the Public realm 🫡