The Rise of the Lone Star Tick

Did Army-funded releases of radioactive ticks ignite an epidemic of tick-borne diseases?

Meet the lone star, Amblyomma americanum, the most badass tick in North America. Lone stars are vicious biters with many competitive advantages over their deer tick cousins. They don’t wait patiently on a grass stalk for passing prey; they have primitive eyes that allow them to stalk mammals. On average, they lay more eggs than deer ticks. All three life stages of the lone star tick feed on humans, sometimes transmitting deadly microbes like the Heartland virus, the Bourbon virus, and Rocky Mountain spotted fever. One bite can trigger life-threatening allergic reactions to red meat.

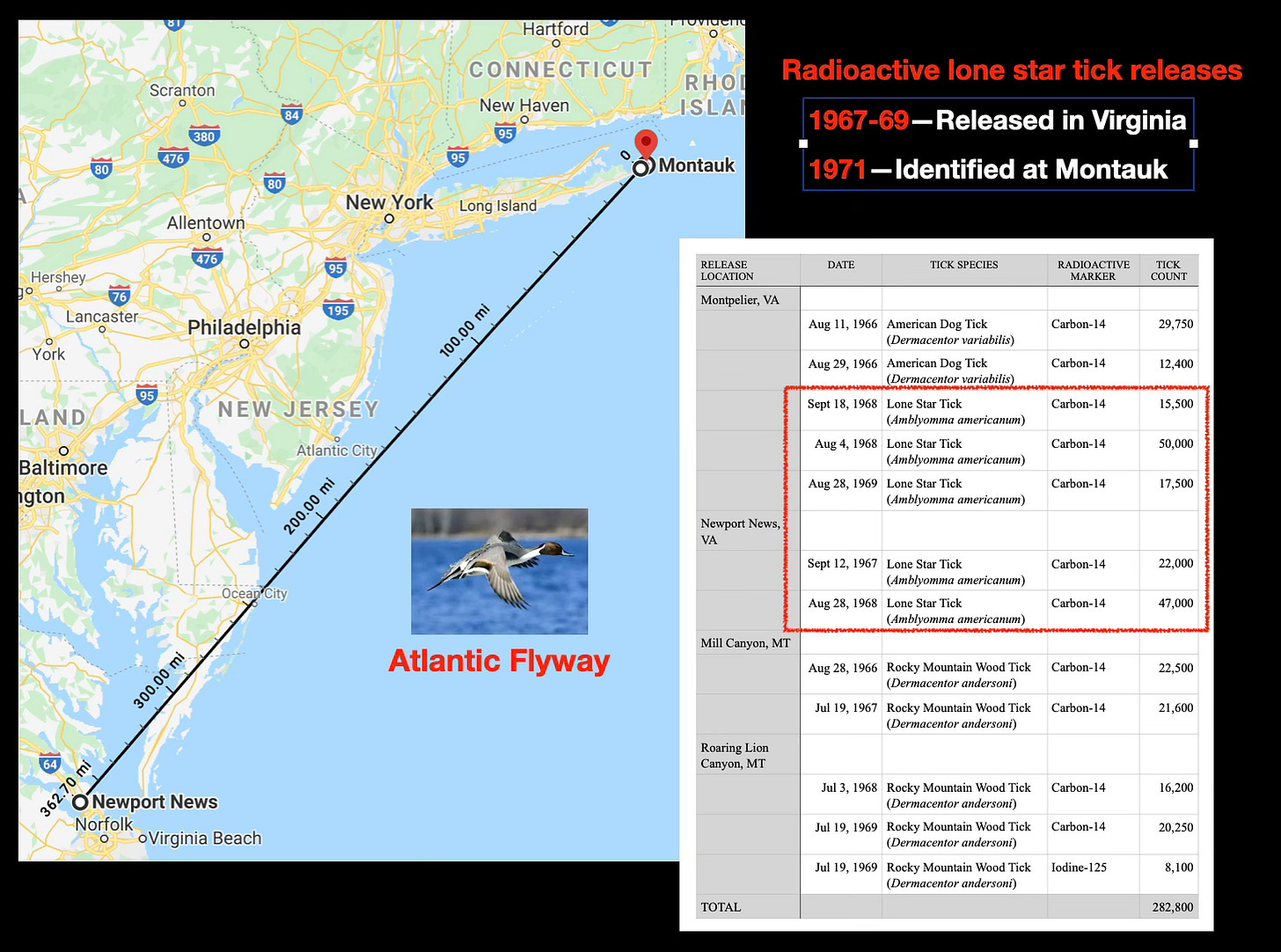

During the last half-century, lone star ticks have rapidly spread from their original territory in the Southeastern U.S. While some researchers attribute this to climate change and shifting land-use patterns [1], I propose that there could be another factor behind this expansion — Army-funded experiments in the late 1960s, where hundreds of thousands of radioactive ticks were released on the Atlantic Bird Flyway. In this series of experiments, a Geiger-counter-like device was used to track how far radioactive ticks crept or traveled by deer or birds over months to years, presumably useful information if the military was using infected ticks as weapons.

During the Cold War, the U.S. developed bug-borne weapons by infecting fleas, ticks, and mosquitoes with disease-causing bacteria and viruses. In the Army’s own words:

In 1953 the Biological Warfare Laboratories at Fort Detrick established a program to study the use of arthropods [ticks, fleas, and mosquitoes] for spreading anti-personnel BW [bioweapons] agents. The advantages of arthropods as BW carriers are these: they inject the agent directly into the body, so that a mask is no protection to a soldier, and they will remain alive for some time, keeping an area constantly dangerous. [2]Dr. Strangelove’s experiments

From 1967-1969, Daniel E. Sonenshine, PhD, an associate professor of parasitology at Old Dominion College and a contractor to the Army’s biological weapons program, raised hundreds of thousands of ticks and released them in Montpelier and Newport News, Virginia, as well as in two canyons near Hamilton, Montana.[3] With help from the Atomic Energy Commission, he also refined a technique for tracking the migration patterns of ticks in the wild by making the ticks radioactive.

NIH scientist Willy Burgdorfer, also a bioweapons contractor, sent him ticks from his collection at Rocky Mountain Laboratory and taught him how to breed large quantities.[4] The first step was to put a rabbit in a linen bag with adult ticks, and then, after twenty-four hours (the time necessary for the majority of ticks to attach), transfer the rabbit to a wire cage and slide a large linen bag over the cage to prevent the engorged ticks from escaping.

After the ticks had fed and mated on a rabbit, Sonenshine picked off the females about to lay eggs and pressed them into a strip of clay laid across a microscope platform. Looking through the microscope lens, he used a 13-gauge syringe to inject the body cavity of each “pregnant” tick with a sugar solution spiked with radioactive carbon-14 or iodine-125 liquid. The females would go on to lay a clutch of one thousand to three thousand eggs, and each larval hatchling would be radioactive for the remainder of its three-stage life.

For the Newport News study, Sonenshine planted poles to partition the woods into forty-seven equilateral squares, placing live animal traps covered with sticky tape at evenly spaced locations. One thousand lone star larvae were then released inside each square. Over the next few months, Sonenshine and his helpers returned to the woods to collect ticks from captured animals, from cloth flags dragged along the ground, and from the sticky tape. Each harvested tick was placed in a vial labeled with the location of the square in which it had been captured.

Back at the lab, a technician would place the vials under a Geiger-counter-like “scintillation detector” to measure the number of original-release, radioactive larval ticks in the batch. Adult and nymph-stage ticks were marked with colored enamel paint and then released into the square where they had been captured. The paint would allow them to be tracked as they migrated.

Over three years, 152,000 radioisotope-tagged lone star ticks were released at the two Virginia sites. The sites were on the Atlantic Flyway, the migratory bird superhighway that runs along the eastern South American and North American coasts. Other studies, some by the CIA and covertly run through the Smithsonian Institution, estimated that some migratory birds could fly from Newport News to Long Island in as little as five days.

Invasive ticks packed with deadly microbes

One problem with releasing invasive, non-native ticks into a new area is that they transmit diseases to which the local animals and humans have no natural immunity. One such disease is Rocky Mountain Spotted fever, Rickettsia rickettsii, the deadliest tick-borne pathogen in the U.S., and a species engineered as a biological weapon by the military. (Deer ticks don’t carry rickettsias, but both tick species used in the flyway studies do.) [5]

There were other risks to this uncontrolled tick release. Were the ticks delivered to Sonenshine free of the many exotic tick-borne microbes housed in Burgdorfer’s lab? Was Sonenshine’s lab secure enough to handle an organism requiring biolevel-3 safety precautions? Did the irradiation of ticks lead to mutations in the microbes living inside the ticks?

Shortly after the experiments ended, the first lone star tick was observed on Montauk, Long Island. Between 1971 and 1976, there were 124 Rocky Mountain spotted fever cases on Long Island. Nationwide, spotted fever cases spiked, reaching record highs from 1969 through 1976. People died.

“Accidents happen”

Of course, the timing of the Army’s lone star tick releases and the spotted fever outbreak around Long Island and Connecticut is circumstantial — but I think about Willy Burgdorfer’s explanation as to why three unusual tick-borne agents suddenly appeared in “Lyme country” in the late 60s.

“Accidents happen,” he said. “Sometimes experiments don’t turn out as planned.”

He also said he was asked to bury the existence of an unidentified rickettsia during his Lyme investigation. His lab notes confirmed this. [6] Given that Burgdorfer was involved in Soneshine’s tick studies from the beginning, one wonders whether this experiment had unintended consequences.

Since the publication of BITTEN, I’ve continued to push for the declassification of tick-borne bioweapons documents, because, if there were “accidents,” they might still be damaging human health and our ecosystem. The disclosure of these 50-year-old documents will save lives and research dollars. Finally, I sincerely hope this information will inspire some fearlessly curious researchers to gather evidence to support or dismiss my hypotheses on the origins of the most controversial disease in America, Lyme disease.

###

Kris Newby is an award-winning medical science writer and the senior producer of the Lyme disease documentary UNDER OUR SKIN. Her book BITTEN: The Secret History of Lyme Disease and Biological Weapons won three international book awards for journalism and narrative nonfiction. Previously, Newby worked for Stanford Medical School, Apple, and other Silicon Valley companies.

If you've found this content useful, please consider supporting it through a small paid subscription. While my posts are free, your paid subscription helps underwrite this independent research. It also helps keep it free for those who cannot afford to pay.

REFERENCES

Some parts of this have been excerpted from my book, “BITTEN: The Secret History of Lyme Disease and Biological Weapons.” Graphics and lone star tick photo by Kris Newby. Rabbit photo from: https://doi.org/10.2307/4587692 Documents are from Willy’s garage, available online here: https://uvu.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/Burgdorfer

[1] Kennedy AC; BCE1; Marshall E. Lone Star Ticks (Amblyomma americanum): An Emerging Threat in Delaware. Dela J Public Health. 2021 Jan 21;7(1):66-71. doi: 10.32481/djph.2021.01.013.

[2] Summary of Major Events and Problems, United States Army Chemical Corps (Fiscal Year 1959),” Rocky Mountain Arsenal Archive.

[3] D. E. Sonenshine et al., “Field Trials on Radioisotope Tagging of Ticks,” Journal of Medical Entomology 5, no. 2 (June 1968): 229–35; D. E. Sonenshine, “The Ecology of the Lone Star Tick, Amblyomma americanum (L.), in Two Contrasting Habitats in Virginia,” Journal of Medical Entomology 8, no. 6 (Dec. 1971): 623–35; and D. E. Sonenshine, “Contributions to the Ecology of Colorado Tick Fever Virus 2: Population Dynamics and Host Utilization of Immature Stages of the Rocky Mountain Wood Tick, Dermacentor andersoni,” Journal of Medical Entomology 12, no. 6 (Feb. 1976): 651–56.

[4] Letter to Willy from Sonenshine, May 10 and 30, 1967, WBC-LD, author’s copy.

[5] Breitschwerdt EB, Hegarty BC, Maggi RG, Lantos PM, Aslett DM, Bradley JM. Rickettsia rickettsii transmission by a lone star tick, North Carolina. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011 May;17(5):873-5. doi: 10.3201/eid1705.101530; Levin ML, Schumacher LBM, Snellgrove A. Effects of Rickettsia amblyommatis Infection on the Vector Competence of Amblyomma americanum Ticks for Rickettsia rickettsii. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2018 Nov;18(11):579-587. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2018.2284; D. E. Sonenshine, “The ecology of ticks transmitting Rocky Mountain spotted fever in the eastern United States, Progress Report, Feb 1, 1966-Jan 31, 1967, US Army Medical Research and Development Command, Contract: DA-49-193-MD-2435, p.ii. “An isolation of this infectious agent was also made from Amblyomma americanum.”

[6] Piller, C, “The ‘Swiss Agent’: Long-forgotten research unearths new mystery about Lyme disease,” STAT, Oct 12, 2016. https://www.statnews.com/2016/10/12/swiss-agent-lyme-disease-mystery/ (accessed Mar 28, 2024)

After 30+ years of fighting the VA for compensation for morgellons Lyme disease from a tick bite at Ft Eustis VA training in 1989 I have finally won 90% compensation. Case still ongoing. They are labeling me as schizophrenic because I believe they experimented on me and others with a bioweapon.

last year I read that lab 259 book, and a couple years before that, I heard the man who worked there and 'armed' ticks, had given his documents to the government before passing away. This was at the start of the scamdemic, and they first thought it was a scam, but it was not. I have not heard anything more about this and wonder, if they will ever get into it