Bioweapons and the Korean War

An interview with Jeffrey Kaye, who lays out the evidence for U.S. bioweapons use during the Korean War.

Germ warfare poster: “The American bandits, paying no attention to the just sanctions of humanity, openly dropped loads of germs on Korea, our country’s northeast, and Qingdao city.” 1952. NIH Digital Collections.

Jeffrey Kaye has spent more than a decade researching the United States’ use of biological weapons during the Korean War (1950 to 1953). When I began “Bitten,” his foundational work helped me understand why, in 1951, the military hired Swiss zoologist Willy Burgdorfer to develop ways of mass-producing germ-laden fleas, ticks, and mosquitoes so that they could be released on enemies.

Kaye believes that the U.S. military significantly enhanced their knowledge on how to weaponize bugs from post-World War II interviews with Japan’s notorious Unit 731 bioweapons group. In exchange for their collaboration, many of these participants were granted immunity from their war crimes, which included inhumane experiments on prisoners.

Kaye’s research paints a disturbing picture of the U.S. military’s decision to use biological weapons on entire populations during the Korean War. The military even crafted a cover-up plan beforehand, which included threats of prosecution against U.S. airmen who confessed to dropping cholera-laced feathers, plague-infected rodents, and spider bombs on China and Korea.

Not surprisingly, Kaye’s evidence challenges the official U.S. narrative on this subject. But in my opinion, he’s pieced together a convincing story, despite the military’s history of document destruction, overclassification, and propaganda.

The takeaway here is that there are important lessons to be learned from this hidden history, namely, how military decisions to develop and release biological weapons were made, and how we can prevent potentially disastrous releases in the future.

What’s your background, and what led you to become an expert on the U.S. military’s use of bioweapons in the Korean War?

I’m a retired clinical psychologist who, for 10 to 15 years, spent time doing assessments and psychotherapy with torture victims who were applying for political asylum in the United States. In the course of that work, I joined with other psychologists and doctors who opposed the U.S. government’s use of torture after 9/11. One thing I read at that time was that the CIA’s “enhanced interrogation” program had been based on the military’s SERE (Survival, Evasion, Resistance, Escape) training on how to deal with possible torture by foreign entities of captured U.S. soldiers, spies, or other officials.

According to Congressional investigators and reporters at the time, the SERE training was originally devised to inoculate U.S. soldiers, officers, intelligence agents and diplomats against the forms of supposed Chinese torture used during the Korean War. Such torture was presumed to be effective in producing false confessions. The most famous case of such alleged false confessions was the accusation that two dozen captured U.S. airmen in the U.S. Air Force and Marines dropped biological weapons on Korea and China beginning in January 1952.

Initially, I believed the assertions about the Chinese use of torture in these cases. But I wanted to see examples of the flyer confessions because I thought it would help me better understand the differences between false confessions of torture and the kinds of narratives my clinical clients were providing me. I thought I could use such data when describing in court (where I was considered an expert witness) whether a particular client was being truthful or not.

But what I discovered was that these flyer confessions were unavailable to the U.S. public. I finally obtained a copy of them from the Imperial War Museum in London. As I continued to examine the details around the biological warfare allegations, I also found that many other primary documents were either missing, still classified or had been destroyed. At first, I was intrigued, but as time went on, I became convinced that the Communist bio war allegations were, in fact, true and that their cover-up constituted one of the more bizarre cases of government censorship I had ever heard of. On my own, I began to research the issue. Since, for the most part, the Korean War germ warfare scandal was considered a dead issue by most U.S. historians, I was quite alone in doing this. Along the way, I discovered a small handful of other researchers also working on this same or closely related issues.

Germ warfare poster: “Flies grow in cesspools and love to buzz around people. They carry countless germs and throw germ bombs everywhere.” 1952. NIH Digital Collections.

Could you provide an overview of the biological weapons operations conducted during the Korean War?

Due to state secrecy, we have only a rough idea of the course of the U.S. biological warfare campaign during the Korean War. But below, I’ve outlined what we know about these events based on previous investigations, U.S. pilot confessions, and various U.S., Canadian, and UK government documents.

The U.S. had been pursuing an offensive biological warfare campaign since they discovered the Japanese had developed a strong program in the mid-1930s. Even before the Korean War started, the Pentagon’s Research and Development Board created the Stevenson Committee (reporting to the Secretary of Defense), which had the task of assessing the need for greater biowarfare research. In June 1950, the Committee concluded that the U.S. needed to significantly step up research in this regard. There was also the fact that the Nazis, too, had made some moves in the bio war field, though not to the extent of the Japanese. Moreover, there was paranoia about what the Soviets might be up to in this regard.

By the end of 1950, the Republic of Korea (South Korea) had a plan for using biological organisms to poison wells and foodstuffs. This bacterial sabotage plan was discovered by the North Korean army when it occupied Seoul in 1950. The plan was consistent with the activities of Japan’s Unit 731 during World War II. Meanwhile, government documents from the Army Chemical Corps (ACC), which led the U.S. biological warfare program at the time, acknowledged that the U.S. state of biological weaponry was still in its infancy. The germ bombs needed greater refinement, except for the “feather bomb” used to release feathers contaminated with organisms to attack enemy food supplies. Experts agreed that using biological organisms in sabotage situations was quite feasible.

Meanwhile, the Army continued to work on perfecting newer versions of old diseases to make them more lethal. This included developing a strain of smallpox that was resistant to vaccines, and, in 1951, Americans were accused of causing a smallpox outbreak in North Korea.

The U.S. plan to deploy aerial biological weapons came after a significant military setback. Beginning in late 1950, Chinese military “volunteers” entered the war and forced U.S.-led troops to retreat from the border with China to below the 38th parallel. At this time, the U.S. seriously considered using nuclear weapons, but in the end, it was deterred because the Soviets had them, too. The use of biological weapons was meant to cause chaos and confusion in the rear of Chinese and North Korean lines and to precipitate panic among the general population.

But because the U.S. military wasn’t yet ready to use many of their newly designed weapons, they turned to the proven biological weapons used by Japan’s Unit 731, weapons that largely relied upon the use of insects to deliver disease-causing pathogens. It has been alleged that former Unit 731 personnel, including leader Shiro Ishii, were directly involved. (A few years before the Korean War, the U.S. had provided immunity from WW2 war crimes to Ishii and his associates, part of a quid pro quo where the ACC scientists at Camp Detrick would learn from Unit 731’s experiences using and experimenting with biological weapons.) To date, we do not have hard evidence of Japanese participation in the biological warfare campaign in Korea, but it does seem highly likely. Some historians have documented how former members of Unit 731 were integrated into postwar Japanese academia and healthcare organizations. Some were known to have offered assistance to U.S. authorities on health issues, including work with the U.S. Army’s 406th Medical General Laboratory, which has been associated with some accusations of involvement in the germ war campaign in Korea.

In any case, the U.S. saw the use of bioweapons in Korea as an experiment in operational use. I have been able to document at least two individuals who lobbied amnesty for Ishii and company, who went on to hold key positions in the Pentagon’s Research and Development Board and Ft. Detrick’s bioweapons research program.

By December 1951, both Canadian and UK biological warfare officials said in their own internal communications that they expected the U.S. to begin using biological weapons. [KN note: Willy Burgdorfer arrived in the U.S. in December 1951, then traveled to Canada for a US/UK/CN bioweapons meeting in 1952.] According to the US flyers’ accounts, the experimental program on aerial bioweapons drops began in December 1951 and continued to expand over the course of 1952. The program involved use of both US Air Force and Marine Corps planes. Drops were made over villages, train depots, and in the rear or near enemy military units. The organisms used included anthrax, plague, and cholera, and possibly encephalitis viruses and hantavirus. The ordnance included bombs with special compartments that opened up as specific elevations or contact with the ground. Spraying of organisms or insects also apparently occurred.

In 2010, the CIA declassified a number of communication intelligence reports from the Korean War. These reports were based on decrypted intelligence intercepts from Communist military radio transmissions. I found two dozen of these that included overheard conversations by Chinese and North Korean military personnel discussing how to react to the U.S. bioweapons attacks, the importance of testing to exclude false reports, and the health consequences some military units were facing because of these attacks. From what I’ve found, the attacks, which were stepped up in May 1952, continued into 1953.

Who was behind these plans, where were the biological weapons assembled, and who dropped them on Korea?

The plans to drop biological weapons on North Korea and China were developed by the Army Chemical Corps and the Air Force Air Materiel Command headquartered at Wright-Patterson AFB in Ohio. As I’ve written before, “A top secret 11 June 1951 U.S. Air Force “Staff Study” on the “BW-CW Program in USAF” aimed at fulfilling an earlier directive (JCS 1837/18) from the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Dated 21 February 1951 — during a period when the U.S. Army was in pell-mell retreat before Chinese forces in North Korea — the Joint Chiefs had called for “a BW-CW combat capability at the earliest possible date.” (Note: This earlier directive, JCS 1837/18, is still classified!)

The Air Force staff study concluded: “BW and CW (biological and chemical weapons) offer a tremendous military potentiality against the overwhelming manpower superiority of the Soviet Union.” The report continued, without explanation, “It may be necessary to use BW against the Chinese suddenly.” (Bold added for emphasis.) Given that U.S. forces were in combat with Chinese troops at the time, this is the closest I’ve seen in a U.S. existing document that biological weapons were even considered for use against the Chinese. Less than seven months after this admission, the U.S. apparently was dropping germ bombs in both North Koran and China. Note: the Air Force doesn’t say, “we don’t have BW ready to use yet, but we’re working on it.” Their report definitely implies that if they have to, U.S. forces can use BW against China if “suddenly” called for.

Such messages continued at the highest levels at the Pentagon. On September 21, 1951, a top-secret memorandum from the Joint Advanced Study Committee to the Joint Chiefs of Staff called for the acquisition of “a strong offensive BW capability without delay,” and use of such weapons “without regard for precedent as to their use.” I would say the final decision for use was very close at this point.

A 1953 Chemical Corps “Summary History” retrospectively explained the situation, “During the period 9 September 1951–31 December 1952, the Chemical Corps was principally concerned with the support of the Korean War and with the improvement of the Bacteriological Warfare (BW) and Chemical Warfare (CW) capabilities of the Armed Forces in the event of an emergency and in defense against radiological attack (RW).” [p. 1]

A key section of the “Summary History” provides what I feel is an excellent description of the situation that faced the biological warfare proponents when it came to running a “crash program” into the use of biological weapons in the Korean War.

“Thanks to the world situation of limited war, the research and development programs were directed at the immediate completion of short-term developments where immediate benefit to operational effectiveness would result. Although some of these developments were admittedly stop-gap measures, such as the M114 biological bomb, they provided something to use if it were required. At the same time developments were accelerated in order to ease the greatest operational deficiencies. The emphasis was therefore placed on end items in all fields, weapons, and munitions for the dissemination of nerve gases (G-agents), and the entire field of biological warfare. [p. 13]”

A similar timeline, with its own documentation, was presented by Nicholson Baker in his book, Baseless: My Search for Secrets in the Ruins of the Freedom of Information Act.

According to depositions provided to Chinese interrogators, Marine Corps Colonel Frank Schwable, and Air Force Colonels Walker Mahurin and Andrew J. Evans, said the Joint Chiefs of Staff gave the order to proceed with the germ warfare campaign in October 1951. The project to develop offensive weapons had been undertaken with the help of both Canadian and UK biological warfare programs, and the knowledge gained, if not actual personnel participation, from former members of Japan’s biological warfare divisions and Unit 731.

The biological weapons were assembled at secret sites, but one Air Force pilot, Lt. Kniss, said that some work on assembling bombs, as well as modifying aircraft for biological weapons took place at Tachikawa Air Base in Japan. Tachikawa was an apt facility, as it was the headquarters for Far East Air Materiel Command (FEAMCOM), which was the primary US Air Force logistics center in Japan, and capable of modifying aircraft.

Other sources, relying on contemporary reports from Japanese Communist sources and historians, have said that the Army’s 406th Medical General Laboratory facilities were also involved in the construction of the weapons prior to delivery. British and American investigators have indicated that “Japanese scientists and staff at Atsugi Airbase Unit 406 along with their two satellite plants in Tokyo and Kyoto that produced the germs bred the insects, and packaged the bombs. In addition, there reportedly were two vector breeding and bomb packaging subordinate to 406th MGL, one at Ishii Shiro’s former underground lab at the Tokyo Military College, and a second located at the Imperial College in Kyoto.” [Powell, Thomas. The Secret Ugly: The Hidden History of US Germ War in Korea (p. 250-51). Edgewater Editions. Kindle Edition.]

According to the head of the Canadian Peace Congress, James G. Endicott (who was also a leader of Canada’s United Christian Church and a former OSS intelligence agent), it was likely that Canada’s own BW program was involved in the shipment of infected insects to the U.S. biowar program during the Korean War. Canada’s insect vector program was headed by Professor Guilford Reed at Queen’s University in Kingson, Ontario, and Reed had organized sources of insect breeding for biological warfare experiments. It is easy to imagine that these, too, could have been leveraged to supply the U.S. BW program in Korea.

In addition, the Special Operations Division at Ft. Detrick collaborated with the CIA to develop weapons for sabotage and covert inoculation. (They had also worked on the construction of a “feather bomb” for use in anti-crop biological warfare.) The head of that division during the Korean War, John L. Schwab, said in a sworn affidavit that Fort Detrick had the capability to wage offensive biowar as early as 1949.

At least one pilot who flew on germ war missions, 1st Lt. Paul Kniss, believed the biological agents were assembled in the U.S. and then flown to the Korean theater. There’s some evidence that this might have been done with at least some of the bioweapons ordnance. A memo marked “Top Secret [-] Security Information [-] Operational Immediate,” was copied to the Air Force Chief of Staff in Washington, D.C., the Commanding General of the Air Division at Travis AFB, and the commanding officers at two units at Kelly AFB in Texas. It described an airlift of “highly classified material” from Kelly to Travis AFB on 19 December 1952. From Travis, the classified materiel departed the U.S. mainland (“ZI departure point”) for Anderson AFB, Guam, and an unspecified place of arrival in Japan. An AMC C-124 cargo plane carried the material, which was to be closely monitored on the trip. Strategic Air Command’s commanding general advised that Travis be ready for the shipment with salvage and security teams, as well as standby aircraft and crew. Travis was to pay special attention to perimeter security for the cargo plane’s arrival. This could have been nuclear munitions, or it could have been BW munitions.

Pilot 2nd Lt. Floyd O’Neal told investigators from the International Scientific Commission that he thought the preparation for the germ weapons “was being done at the Aberdeen Proving Grounds in Maryland.” Aberdeen Proving Grounds was also the headquarters of Edgewood Arsenal, which was closely associated with Detrick’s chemical and biological warfare programs. The bombs were being brought to the Far East “by air transport, every 2 weeks or so.” His account appears to corroborate the claims of Lt. Kniss. From my standpoint, it is not necessary to believe there was only one way in which weapons were procured. As it was an experimental program, different agents, delivery devices, and munitions could have originated in different departments or supply routes. It is important that this campaign originated in a climate of perceived military necessity.

Furthermore, we know that as early as December 1951, some 1,200 biological bomb assemblies were flown to England and Libya as part of an offensive anti-crop biological weapons program called Steelyard, aimed for use against the Soviet Union.

So far as I understand, the bombs were dropped by U.S. Air Force and Marine Corps airplanes, including B-26s, B-29s, F-86s, and F7F aircraft (Tiger Cats). The airmen and navigators were specially briefed, and the germ bomb loads were handled by Special Mission forces. Besides bombs specially created for insect or feather material delivery on the Japanese Unit 731 model, the U.S. propaganda bomb was apparently modified to drop BW vector material instead of leaflets on enemy formations, railways, reservoirs, and towns. Disease agents were placed on a number of different insect species, spiders, and also small mammals (voles), in addition to feathers, pieces of paper, etc. The BW offensive was admittedly considered “experimental” in the period from approximately December 1951 to May 1952. Afterward, the air campaign was said to be extended and better integrated into offensive operations, including the addition of night bombing raids. Besides bombs, aerial spraying of infectious material, and possibly certain kinds of insects, also took place.

There was another source of biological warfare that did not come from airdrops. This involved the use of sabotage to spike water, food areas, and military living quarters with contaminants, such as cholera. The contaminants would have been hand-delivered in such circumstances.

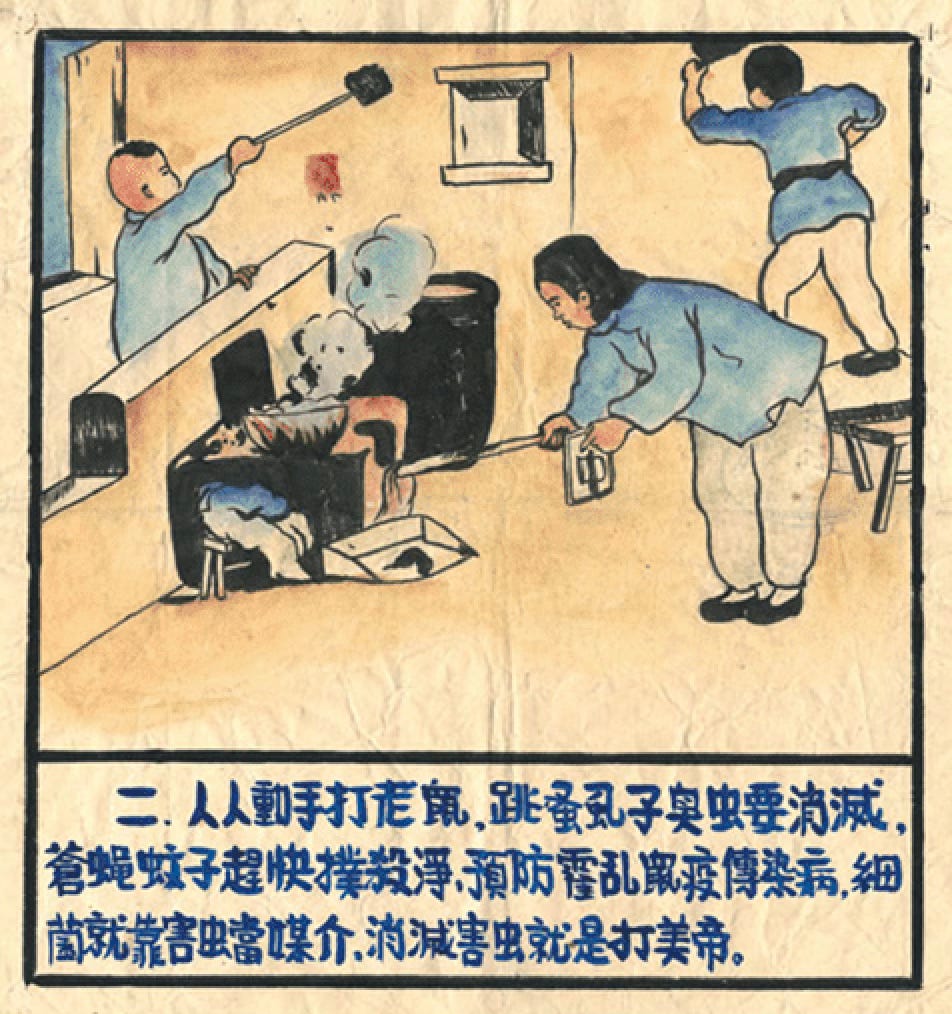

Germ warfare poster: “Germs rely on pests as a way to spread diseases. To eradicate pests is to defeat the American imperialists.” 1952. NIH Digital Collections.

What was the impact on the Korean population?

There was an impact on both Korean and Chinese populations, as the weapons were dropped on both countries, though the Chinese area of operations was limited to northeast Manchuria. This was not the first time that China had been exposed to bioweapons. They had already experienced insect germ warfare attacks in WWII from Unit 731. There were also many Korean Communists fighting with Chinese forces against the Japanese at this time, including Kim Il Sung, and they also had knowledge of the germ attacks and the lessons learned from dealing with them. As a result, both China and North Korea had well-developed medical public health procedures, particularly in the military, to deal with the attacks. China also launched a huge public health campaign organized around the idea of foiling the germ war attacks. I recently wrote about that.

The North Korean government was far more constrained in terms of large-scale response, as it was under near constant massive bombardment throughout much of the war, and their cities had largely been destroyed. But awareness of what to do in the countryside, led by military health units and public health instructions, meant that the population did not seem to panic. There are a couple of reports in the CIA-released communications intelligence (COMINT) gathered by the NSA (and its predecessor, the AFSA, Armed Forces Security Agency) that reported that there was confusion and some panic as military units were first attacked by infectious agents. There was also the problem of false reports. At least one of the declassified COMINT reports described such a false report, including the method by which all reports were verified. Separating out false reports was a military necessity, as resources inside the military were scarce, and the Korean People’s Army would not have wished to waste time or resources responding to false reports.

It's not known what the mortality or sickness rate was among the population in the wake of the attacks. Early reports from investigators of the International Association of Democratic Lawyers indicated that there were fatalities. The International Scientific Committee (led by British scientist Joseph Needham) also reported on some fatalities. But by most accounts, the Chinese and North Korean governments kept casualties a wartime secret, and that has remained so over the years.

What happened to the U.S. airmen involved?

All the captured U.S. airmen who made confessions about the use of biological weapons were repatriated to the United States in Operation Big Switch in September 1953. All, or most, of these flyers were sent to Tokyo for medical and initial psychiatric exams. They were also interviewed by military intelligence, and depending on their service branch, the Army’s Counter-Intelligence Corps (CIC), Air Force Office of Special Investigations, and the Marine Corps own Board of Inquiry. CIA, Office of Policy Coordination (covert ops), and the Army’s Criminal Investigative Division also apparently did their own debriefings of the flyers. There may have also been FBI interrogations later. One historian has indicated that the FBI kept tabs on these men for the rest of their lives. The returning personnel were also subjected to multiple psychiatric examinations or indoctrinations. Some military personnel (non-flyers, Army types who were not involved in the BW campaign) were subjected to Operation Artichoke mind control experiments at the Army’s Valley Forge Hospital in or around the summer of 1953. It is possible that some of the flyers were also subjected to CIA mind control interrogations, but I have no evidence of that.

After they left Japan, the flyers were sent back to the States on the MSTS Howze, where they were kept isolated from other returning POWs or military personnel. There was a “Joint Intelligence Processing Board” aboard the Howze, chaired by Lt. Col. Robert Matthews of the CIC. According to what Matthews told historian Raymond Lech, he had assisted Schwable in the rewriting of his recantation of this confession to the Communists. It’s likely that he or other CIC (or other intelligence personnel) did the same for the other airmen. Also, Matthews indicated that the flyers were all told that they had to be careful what they said, as they could be indicted for treason for their behaviors under captivity (i.e., confessions). Hence, while ultimately all the airmen recanted their tales of U.S. BW use in Korea/China, it was done under threat of prosecution. Some decades later, in a documentary for Al Jazeera, Kenneth Enoch walked back the allegations that he had been tortured by the Chinese.

None of the airmen were put on trial, and none were court-martialed. One high-ranking flyer, Colonel Schwable, who had also been Chief of Staff of the First Marine Aircraft Wing, was subjected to a Board of Inquiry by the Marine Corps. This was not a formal court-martial, however, and Schwable was exonerated of any wrong-doing. But his Air Force career was all but over.

Most of the Korean airmen retired from the military and went into the private sector or lived secluded, low-key lives. A few hung onto military jobs for some years, like Schwable and Evans. Walker Mahurin went on to do classified work that may have been related to the U-2 project and had a working relationship with Richard Bissell of the CIA.

So far, I only know of two of the captured airmen who went on to write books about their experiences, Walker Mahurin and William (Bill) Fornes. Oddly, in his own book, Fornes laid out a narrative that denied he had ever made a bioweapons confession at all. I wrote about Fornes here.

How would you summarize the U.S. military’s coverup playbook in response to the negative publicity that these attacks generated?

I was surprised to discover that the U.S. had anticipated that information about the germ war would leak out. They laid the groundwork for the story about tortured evidence and false confessions before any confessions had ever been made! They discussed in the highest councils of the covert world (at the time, in Truman’s Psychological Strategy Board and Eisenhower’s psychological warfare Operations Coordinating Board) how to spin the stories coming out, and how to combat the revelations, especially of Needham’s report for the International Scientific Commission. Even more alarming, they initiated a covert program to “Destroy and Counter-Exploit the Soviet Bacteriological Warfare Myth.” The State Department and military gave the CIA primary responsibility, calling for a program that, in their own words, explained: “counter-propaganda and personalized seduction and coercion will be initiated as a matter of urgency against persons and groups where the Soviet campaign has been especially effective.”

There were a number of ways that the publicity about the germ warfare was combatted. There were prosecutions of journalists. There were false stories planted by CIA agents in the press. There was the destruction of mail coming into the country that would counter U.S. propaganda. There may have even been murders. Remember, this all took place at the height of the Cold War McCarthyite period when anybody arguing that the Communist side had any argument worth listening to would be labeled an enemy of the people and blacklisted.

What was the most surprising thing you’ve discovered during this investigative journey?

I think the moment I was most surprised was when I learned that the airmen had been briefed prior to their germ war missions that if they were captured, they were free to discuss anything and everything about what they knew! Up to that point, there appeared to be only two possible narratives surrounding the controversy that was the flyers’ confessions. One, backed by the U.S. government, was that the flyer’s confessions had been coerced by torture, possibly even by drug-induced brainwashing by their Chinese and North Korean captors.

The other narrative simply took the Communists at their own word: there had been no torture or coercion, and the confessions were the result of remorse on the part of the airmen. Up until a few years ago, I thought I had developed a more nuanced theory—that the flyers had been under the stresses of confinement and remorse over the use of germ weapons, so that when these senior officers talked of the bioweapons program, they could say that it was under some coercion.

All the above had to be thrown out when I discovered that the Pentagon had given the airmen special permission to talk about anything they knew, including secrets, to their captors. This seemed incredible to me, but upon reflection, it did make some sense. The military had invested a great deal in these specially trained personnel, and it did not wish to see them damaged during captivity, especially if subjected to intense interrogation or torture. I also found out that such an order (to talk if captured) had been given in other instances regarding secret operations. From an operational standpoint, the truth was that at least some, if not most men, were expected to talk, and after a short period of time, whatever they said was not expected to negatively impact program security, given their disinformation plans.

In any case, this finding changed the way I looked at the POW confessions, or at least gave it an important nuance. For one thing, none of the airmen ever indicated (until after their repatriation, and then only Schwable and Mahurin) that such instructions had been given to them. (Mahurin had indicated in his book, Honest John, that the instructions had also been given to fairly novice or junior flyers, as well as people such as himself.) This meant that the flyers had, in fact, held back certain things, for whatever reasons. This was the finding of the CIA’s MKULTRA psychiatrist, Louis Jolyon West, who had been involved in the investigations of flyers’ behavior soon after they returned home. West felt that there had been a spectrum of responses to enemy interrogation among the flyers (and all the POWs more generally), from strong resistance to interrogation to easy answers. In general, no one was ever purely non-responsive to interrogation or completely cooperative, and each prisoner tried in their own way to maintain their integrity.

One thing the revelation from the Schwable Court of Inquiry did do was demolish the theory that the confessions had occurred because of Communist torture. That narrative did not make sense anymore, even while some forms of coercion still may have been used to “soften up” more recalcitrant officers.

How hard has it been to obtain this information? What is your takeaway on the ongoing classification of these records?

I wasn’t the first investigator to look at this historical episode. There were two books that laid the groundwork for my own. One was Peter Williams and David Wallace’s 1989 book on Unit 731. The British edition of the book had a chapter on the controversy over U.S. use of germ warfare in the Korean War. The U.S. edition was missing that chapter. This was my first experience of the censorship surrounding this topic. Canadian scholars Stephen Endicott and Edward Hagerman put out a book specifically on the U.S. germ warfare charges. They were the first to include Chinese documentation. The same year their book came out, U.S. Cold War scholars Kathyrn Weathersby and Milton Leitenberg published an analysis of twelve supposed Soviet documents they claimed showed the Communist charges were a “hoax” manufactured by the Soviets and the North Koreans. Their version of events, based on shoddy, biased scholarship, stole the thunder from Endicott and Hagerman’s book.

Another book that influenced me was Dave Chaddock’s 2013 publication, “This Must Be the Place: How the U.S. Waged Germ Warfare in the Korean War and Denied It Ever Since.” I even wrote up a book review on it some ten years ago. Chaddock’s arguments against those who argued the Communist evidence was a “hoax” seemed very cogent to me. The book influenced my thinking on the subject, and along with Endicott and Hagerman’s own book, set me down the road of gathering my own evidence to either buttress or disprove their own arguments.

I decided to do all I could to find primary sources, despite my language limitations and financial constraints that limited travel, access to archives, etc. In particular, I was highly motivated to find some of the original documents surrounding the controversy, namely the September 1952 report of the International Scientific Commission, headed by Joseph Needham, who visited North Korea and China. In addition, I could find no copy of the “confessions” by captured U.S. flyers published by the Chinese in 1952 and 1953. There was one exception, and that was the depositions of Colonel Frank Schwable. The cogency of the latter led me even more to seek out those published confessions, which I finally found at the Imperial War Museum in London.

My documentation search has been hampered by long-time censorship, the fact that many documents remain classified or have been destroyed. Important documents also resided in private archives, and a fire destroyed many U.S. military documents from the period, held by the National Archives. Moreover, in 1950, the U.S. government destroyed related books, magazines, journals, and other material sent via third-class mail to the United States from the Soviet bloc and China. The early work of John W. Powell in China, was unavailable to me and is difficult to access. Luckily for me, the rise of online archival websites, including those that digitized historical newspaper stories, has been of great assistance.

Declassified documents show that the U.S. made a concerted attempt to falsify the historical record of the U.S. biowar program and instituted both overt, legalistic, and covert action programs to suppress the truth about the secret U.S. program of using germ warfare in the Korean War.

I should also note that I am not the only contemporary author to explore the controversy of the U.S. use of bioweapons in Korea. Thomas Powell, the son of John W. Powell, has published some powerful work in the journal Socialism and Democracy that has deconstructed the attempts by U.S. scholars to portray the reality of the U.S. germ warfare attacks as a well-constructed hoax. Five years ago, author Nicholson Baker also published a book about his own personal odyssey exploring the existing documentary record surrounding the germ war, and the U.S. biowar program more generally. His book, Baseless: My Search for Secrets in the Ruins of the Freedom of Information Act, also documents the difficulties of using the Freedom of Information Act to get at the truth. He also corroborates much of what I write about, though he came to somewhat different conclusions. In the end, he felt some version of the use of bioweapons did occur, and not just in the Korean War.

Germ warfare poster: A soldier, doctor, and worker attack the rat-man with the weapons of their trade—gun, fumigation sprayer, and shovel. The caption reads: “Under the attack of the Chinese and Koreans, as well as peace-loving people all over the world, the heinous crimes of the Americans cannot save them from their inevitable defeat.” 1952. NIH Digital Collections.

Why is this story important?

The answer to this question flows from my answer to the previous question. The suppression of a major war crime—the U.S. use of weapons of mass destruction, no less—is directly related to the ongoing battle to get the truth about what our government does. Today, both China and North Korea have nuclear weapons. The position of the U.S. is that these governments are our enemies, and there is an ongoing military build-up, with consequent political tensions, surrounding U.S. relations with these countries. However, the American population does not have accurate information about the true history of U.S. conflict with these nations. As a result, the U.S., China, and North Korea (and probably Russia) have historical conflicts that could ignite a nuclear world war, killing hundreds of millions of people.

In addition, the shadow of biological war hangs over the planet. Research pertaining to biowarfare may have had a role in the outbreak of Covid-19. Even if the latter were spillovers from nature and not related to any human or lab error, the fear of the latter and the anxieties triggered by fear of biological warfare have distorted the response to dangerous pathogens. In addition, the truth around ongoing research into biological warfare remains clouded. Revealing the truth about the past misuse of such knowledge can only assist in opening up our understanding of present work along these lines. Finally, there is also the question of government transparency and the openness of society. I personally don’t think it is an exaggeration to say that I have been working on one of the most important stories ever to be undertaken by an independent investigative journalist. The implications of this story are staggering.

I often say that the Korean bug-borne weapons program was a prequel to the Cold War operations detailed in my book “Bitten.” What was your takeaway when you first read my book?

I was very excited when I first discovered your work! Not only did it address the biowarfare program of the 1950s, but it also dealt with issues like state secrecy, the manipulation or destruction of documents, and the blowback from military programs on biowarfare that very well seem to have allowed for the release of organisms into the environment. Whatever might have been released around Lyme, CT, has negatively affected the lives of millions and led to an untold number of deaths. Personally, I was very interested in Willy Burgdorfer’s biography and his experience working as a bioresearcher in the U.S. germ war program. From my past work as a psychologist, I was intrigued by how work in the bio war area affected the men and women who labored in that field. My own research has shown that there was great unease in the scientific community surrounding this, and even among those who worked at Detrick. My takeaway from your book regarding Burgdorfer is that there was a great deal more that happened that we just don’t know.

You publish an excellent substack, “Hidden Histories,” on Korean War germ warfare. What’s next?

Thanks for your kind words about HH. My next project is to collect my own research into book format. I believe that is necessary in order to press my case on this issue to the world, not to mention provide a kind of one stop site that integrates the various strands of my evidence. I only hope I can do half as good a job as you did, and as Tom Powell and Endicott/Hagerman did in their books.

***

For more on biological weapons, subscribe to Kaye’s Substack and Medium newsletters.

https://jeff-kaye.medium.com

***

Kris Newby is an award-winning medical science writer and the senior producer of the Lyme disease documentary UNDER OUR SKIN. Her book BITTEN: The Secret History of Lyme Disease and Biological Weapons won three international book awards for journalism and narrative nonfiction. Previously, Newby worked for Stanford Medical School, Apple, and other Silicon Valley companies.

If you’ve found this content useful, please consider supporting it through a small paid subscription. While you can read any of my posts for no charge, a paid subscription helps underwrite this independent research. And it keeps it free for those who cannot afford to pay.

"Willy Burgdorfer "

the wily Willy: I rather think his name was added to Borrelia burgdorferi; a spirochaete; the putative organism that is attributed to Lyme Disease; https://dermnetnz.org/topics/lyme-disease

as I understand it called after the town of Lyme; just north of Plum Island; home it was said of US biowarfare research; it has been suggested they were trying to "weaponise" ticks; two different schools of thought; that Lyme disease might have originated in the bioweapons programme on Plum Is; the opposite school says that is a conspiracy theory;

spirochaetes are remarkable things; syphilis is caused by a spirochaete; treponema pallidum which can change into many, many forms; most think of it as a wriggly spirochaete only.

Thank you for this fascinating interview. I was alerted to your book by Jeffrey Kaye, who I follow with great interest. I found your work an intriguing and disturbing read - as both you and Jeffrey Kaye conclude, there are still missing and hidden pieces to this important story. The unceasing readiness of our states to produce, experiment with and sometimes use biological and chemical weapons is truly sinister.