What Lurks in the Grass

The exquisite anatomical design that enables ticks to suck your blood.

An excerpt from BITTEN: The Secret History of Lyme Disease and Biological Weapons.

A tiny eight-legged creature slowly crept up a blade of beach grass. It was about the size of a poppy seed, armored with a hard, shiny shell.

When it reached the blade’s tip, the rear legs clamped down and the creature raised its forelegs high and wide toward the sky. It was blind, and it experienced the world through these forelegs. [1]

There, a few sensory bristles, perfected over more than 120 million years of evolution [2] could detect temperature changes, humidity, ammonia in sweat, and carbon dioxide in breath. The tick was sniffing the air for these signals, waiting for a warm-blooded animal to pass by. It could wait hours, days, or even months, swaying with the sea breeze.

Haller’s organ, located on the front legs of ticks, is a group of chemosensitive cells that detect odors, carbon dioxide, and heat.

When the carbon dioxide from my breath wafted by, the tick sprang to attention. It began waving its foreleg claws and snagged the skin of the passing mammal. In an instant, the glands below its claws began oozing a fatty, sticky substance that helped it hold onto my leg.

The leg of an Asian long-horned tick, showing the sticky pad and grappling claws at the tip.

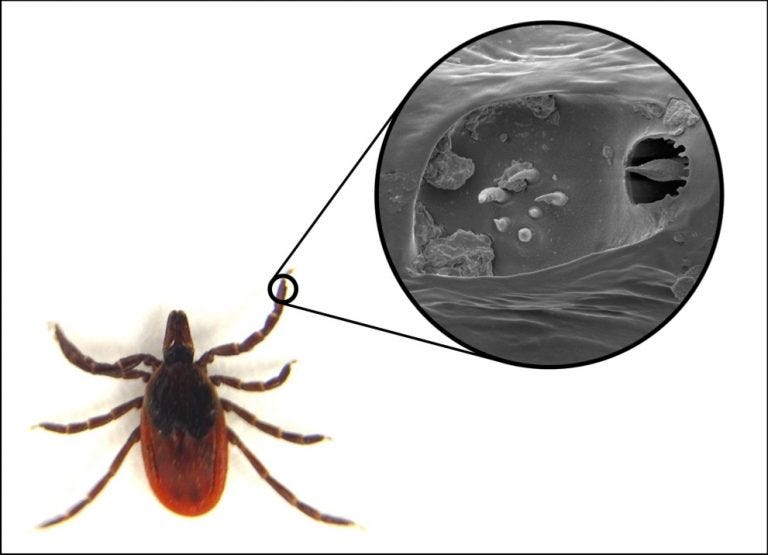

Then it began crawling upward, its senses attuned to locate a protected, blood-infused patch of skin. The tick found the perfect spot at the nape of my neck, hidden under my hair. The back legs elevated the tick’s mouthparts at the perfect striking angle, and its three-part jaw telescoped down toward my skin.

The feeding apparatus of a castor bean tick.

First, the top two cutting mouthparts gently scraped the surface while releasing a numbing agent. Then, by rocking its body back and forth, the tick began digging through my tough outer layer of skin. Its bottom jaw, shaped like a shovel and backed with harpoon barbs, slid into the hole to anchor the drilling operation.

Once a feeding hole was established, the tick’s salivary glands secreted chemicals into the wound site. A cement-like substance, coated with a protein that made it invisible to my immune system, hardened into a funnel and anchored the jaws to the hole. As blood pooled at the bottom of the hole, the tick’s throat muscles began a pumping action: saliva flowed out, my blood flowed in. Chemicals in the saliva included a clot-dissolving fluid that prevented the wound from scabbing over, as well as others that suppressed my immune system defenses.

While the tick fed, it released into my bloodstream the microbial hitchhikers floating inside its body. Its salivary chemicals would blunt my immune defenses for a week or more, allowing these foreign invaders to multiply with little resistance.

Over the next few days, the tick’s body ballooned with blood. Its weight increased one hundred-plus times, [3] and when the tick could hold no more, it dropped to the ground.

The deer tick feeds for multiple days, sometimes expanding 100 times its body weight.

I remained oblivious to the encounter. Another tick bit my husband. Both ticks would go on to molt or lay several thousand eggs, and the cycle would begin again, perhaps repeating for another million years. We had been bitten by unseen ticks harboring an unknown number of disease-causing organisms. This tick bite would rob me of my good health and send me on an investigation into an almost unimaginable possibility: that I was collateral damage in a biological weapons race that had started during the Cold War.

###

Kris Newby is an award-winning medical science writer and the senior producer of the Lyme disease documentary UNDER OUR SKIN. Her book BITTEN: The Secret History of Lyme Disease and Biological Weapons won three international book awards for journalism and narrative nonfiction. Previously, Newby worked for Stanford Medical School, Apple, and other Silicon Valley companies.

If you’ve found this content interesting, please consider supporting it through a small paid subscription or donation. While you can read my posts for free, a paid subscription helps underwrite this independent research. And it keeps it free for those who can’t afford to pay.

Sources:

1. John L. Capinera, ed., Encyclopedia of Entomology (Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer, 2008), 3780.

2. Dana K. Shaw et al., “Infection-derived Lipids Elicit an Immune Deficiency Circuit in Arthropods,” Nature Communications 8 (Feb. 14, 2017): 14401.

3. Capinera, ed., Encyclopedia of Entomology, 3785.

Image credits:

Tick head courtesy of Rocky Mountain Laboratories, NIAID, NIH. Illustration by Kris Newby.

Haller’s organ picture courtesy of T Josek, microscopist, University of Illinois.

The leg of an Asian long-horn tick from Phurchhoki Sherpa, research assistant, Purdue University. https://ecommons.cornell.edu/browse/author?value=Sherpa,%20Phurchhoki

The feeding apparatus of the European castor bean tick © courtesy of Dania Richter, Technische Universitaet Braunschweig, Germany.

Tick engorgement illustration courtesy of NIAID/NIH.

A special thanks to Otis Haschemeyer, the Stanford writing instructor who had the brilliant idea to start out my book like JAWS, from the point of view of the predator.

Facinating and shudder-inducing. Thank you.